H2 Suppresses Cardiac Hypertrophy through Antioxidative PathwaysScientific Research

Hydrogen (H2) Inhibits Isoproterenol-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy via Antioxidative Pathways

Yaxing Zhang

1Department of Physiology, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Jingting Xu

1Department of Physiology, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Xinhua College, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Zhiyuan Long

1Department of Physiology, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Chen Wang

1Department of Physiology, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Ling Wang

1Department of Physiology, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Peng Sun

1Department of Physiology, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Ping Li

1Department of Physiology, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Tinghuai Wang

1Department of Physiology, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Abstract

Background and Purpose: Hydrogen (H2) has been shown to have a strong antioxidant effect on preventing oxidative stress-related diseases. The goal of the present study is to determine the pharmacodynamics of H2 in a model of isoproterenol (ISO)-induced cardiac hypertrophy.

Methods: Mice (C57BL/6J; 8–10 weeks of age) were randomly assigned to four groups: Control group (n = 10), ISO group (n = 12), ISO plus H2 group (n = 12), and H2 group (n = 12). Mice received H2 (1 ml/100g/day, intraperitoneal injection) for 7 days before ISO (0.5 mg/100g/day, subcutaneous injection) infusion, and then received ISO with or without H2 for another 7 days. Then, cardiac function was evaluated by echocardiography. Cardiac hypertrophy was reflected by heart weight/body weight, gross morphology of hearts, and heart sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and relative atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) mRNA levels. Cardiac reactive oxygen species (ROS), 3-nitrotyrosine and p67 (phox) levels were analyzed by dihydroethidium staining, immunohistochemistry and Western blotting, respectively. For in vitro study, H9c2 cardiomyocytes were pretreated with H2-rich medium for 30 min, and then treated with ISO (10 μM) for the indicated time. The medium and ISO were re-changed every 24 h. Cardiomyocyte surface areas, relative ANP and BNP mRNA levels, the expression of 3-nitrotyrosine, and the dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) were examined. Moreover, the expression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 (ERK1/2), p-ERK1/2, p38, p-p38, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), and p-JNK were measured by Western blotting both in vivo and in vitro.

Results: Intraperitoneal injection of H2 prevented cardiac hypertrophy and improved cardiac function in ISO-infused mice. H2-rich medium blocked ISO-mediated cardiomyocytes hypertrophy in vitro. H2 blocked the excessive expression of NADPH oxidase and the accumulation of ROS, attenuated the decrease of MMP, and inhibited ROS-sensitive ERK1/2, p38, and JNK signaling pathways.

Conclusion: H2 inhibits ISO-induced cardiac/cardiomyocytes hypertrophy both in vivo and in vitro, and improves the impaired left ventricular function. H2 exerts its protective effects partially through blocking ROS-sensitive ERK1/2, p38, and JNK signaling pathways.

Introduction

Heart failure is a global pandemic affecting an estimated 26 million people worldwide, posing an enormous burden to both individuals and society (Ambrosy et al., 2014). Heart failure is often preceded by left ventricular hypertrophy, which is characterized by an increase in the size of individual cardiac myocytes and re-expression of fetal cardiac genes, such as atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP; Magga et al., 1998Heineke and Molkentin, 2006). Although cardiac hypertrophy has traditionally been considered as an adaptive response required to sustain cardiac output in response to stresses, long-standing hypertrophy will eventually lead to congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, and sudden death (Frey and Olson, 2003).

Increasing evidence suggests that diverse pathophysiological stimuli, including neurohumoral activation [such as angiotensin II (ANG II) and β-adrenoceptor stimulation], hypertension, ischemic heart diseases, myocarditis, and diabetic cardiomyopathy, will contribute to cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure partially via inducing the production of excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS; Li et al., 2002Zhang et al., 2007bZhang et al., 2015). The nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and mitochondria have been proposed as primary sites of ROS generation (Dai et al., 2011a). ROS generated by NADPH oxidase was shown to stimulate and amplify mitochondrial ROS production and induce mitochondrial dysfunction, which can be reflected by the depression of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP; Zorov et al., 2000Dai et al., 2011a). The excessive accumulation of ROS subsequently activates downstream ROS-sensitive signaling pathways implicated in pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Therefore, blocking ROS will improve mitochondrial function and block downstream hypertrophic signaling, thus preventing the development of cardiac hypertrophy and progression to heart failure. Consistent with this notion, recent studies revealed that strategies targeted ROS and downstream signaling pathways modulated by ROS could be a better approach to improve cardiac hypertrophy (Burgoyne et al., 2012).

Molecule hydrogen (H2), which is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, and flammable gas, has attracted considerable attention for improving oxidative stress-related diseases (Ohta, 2015). We recently revealed that intraperitoneal injection of H2 protects against vascular hypertrophy induced by abdominal aortic coarctation (AAC) in vivo, and H2-rich medium attenuates proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) stimulated by ANG II in vitro (Zhang et al., 2016). Moreover, H2 also has important role in protecting against heart diseases. Inhalation of H2 attenuates left ventricular remodeling induced by intermittent hypoxia (Hayashi et al., 2011Kato et al., 2014), and improves cardiac hypertrophy after germinal matrix hemorrhage in neonatal rats (Lekic et al., 2011). However, the effects of H2 on cardiac hypertrophy induced by β-adrenoceptor stimulation and the related signaling mechanisms still remain unclear. The aims of this study are, therefore, to determine the effect of intraperitoneal injection of H2 on isoproterenol (ISO)-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo, and the effect of H2-rich medium on ISO-induced H9c2 cardiomyocytes hypertrophy in vitro, as well as to identify the molecular mechanisms that may be responsible for its putative effects.

Materials and Methods

Drugs and Chemicals

H2 (99.999%; Guang Zhou Guang Qi GAS Co., Ltd, Guangdong, China) was stored in the seamless steel gas cylinder, and it was injected into an aseptic soft plastic infusion bag (100 ml; CR Double-Crane Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd, Anhui, China) under sterile conditions immediately before intraperitoneal injection. ISO (I5627, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in normal saline (5 mg/10 ml) under sterile conditions immediately before subcutaneous injection, and dissolved in double distilled water as 10 mM stock solution 30 min before use. The antibodies against extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), p-ERK1/2, p38, p-p38, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), and p-JNK, p67 (phox) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The antibody against β-actin was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-α-actin antibody was from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The antibody against 3-nitrotyrosine was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). JC-1 was from Beyotime Biotechnology (C2006, Jiangsu, China).

Preparation of H2-rich Medium and Measurement of H2 Concentration

H2-rich medium was prepared as previously described (Zhang et al., 2016). The concentration of H2 was measured by MB-Pt reagent (generously provided by Ming Yan, Shanghai Nanobubble Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) as previously described (Zhang et al., 2016). The H2 concentration in our H2-rich medium was no less than 0.6 ppm (0.6–0.9 ppm).

Cell Culture and Treatment

H9c2 rat cardiac myoblasts (a cardiomyoblast cell line derived from embryonic rat heart tissue; generously provided by Prof. Hongliang Li, Wuhan University, China) were grown in DMEM containing 5.5 mM glucose as described previously (Jeong et al., 2009). To induce hypertrophy, cells were serum starved for 18 h in DMEM containing 1% FBS, and then treated with 10 μM ISO for 48 h (Jeong et al., 2009). In order to investigate the effect of H2 on the blockage of ISO-induced hypertrophy, H2-rich medium was added 30 min before ISO administration, the medium, and ISO were re-changed every 24 h, and cardiomyocytes hypertrophic response was examined after 48 h of ISO challenge (Jeong et al., 2009).

Animal Model of Cardiac Hypertrophy and Treatment Protocol

The C57BL/6J mice (aged 8–10 weeks, male) were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of Sun Yat-sen University. The animals were housed with 12-h light–dark cycles and allowed to obtain food and water ad libitum. All experimental procedures and protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University), and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH publication NO. 85-23, revised 1996).

Cardiac hypertrophy was induced by subcutaneous injection of ISO (0.5 mg/100g/day) for 7 days as previously revealed (Tshori et al., 2006). Mice were randomly assigned to four groups: Control (Con) group (n = 10), ISO group (n = 12), ISO plus H2 group (n = 12), and H2 group (n = 12). H2 was given at the dose of 1 ml/100g/day by intraperitoneal injection as previously described (Huang et al., 2013Zhang et al., 2016). Mice in ISO plus H2 group and H2 group received H2 consecutively for 7 days before receiving ISO, and continued for another 7 days. On the 8th day, mice in ISO group, and ISO plus H2 group received ISO for 7 days until animals were sacrificed on the 15th day. After sacrifice, hearts were excised, rinsed with ice-PBS, and blotted dry. Hearts were weighed; the heart weight/body weight (HW/BW) ratios were calculated and expressed as milligrams HW per gram BW. Then hearts were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen within minutes and stored at -80°C until analyzed.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed to assess left ventricular function before sacrificed on the 15th day in a blinded manner. Mice were anesthetized with 1.5–2% isoflurane, and hearts were visualized using a RMV707B (30 M Hz) scan-head interfaced with a Vevo-2100 high frequency ultrasound system (VisualSonics Inc., Toronto, Canada) at least three times for each animal indicated (Webb et al., 2010).

Histological Analysis

Hearts were excised, washed with ice-PBS, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and cut transversely close to the apex cordis to visualize the left and right ventricles. Several sections of heart (4–5 μm thickness) were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathology and then visualized by light microscopy.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunostaining, anti-sarcomeric α-actin antibody was used to assess the cell surface area of H9c2 cardiomyocytes as described previously (Akimoto et al., 1996). To assess 3-nitrotyrosine levels in heart, which can reflect formation of ONOO–, primary antibody against 3-nitrotyrosine (1:50) was used as previously described (Zhang et al., 2011).

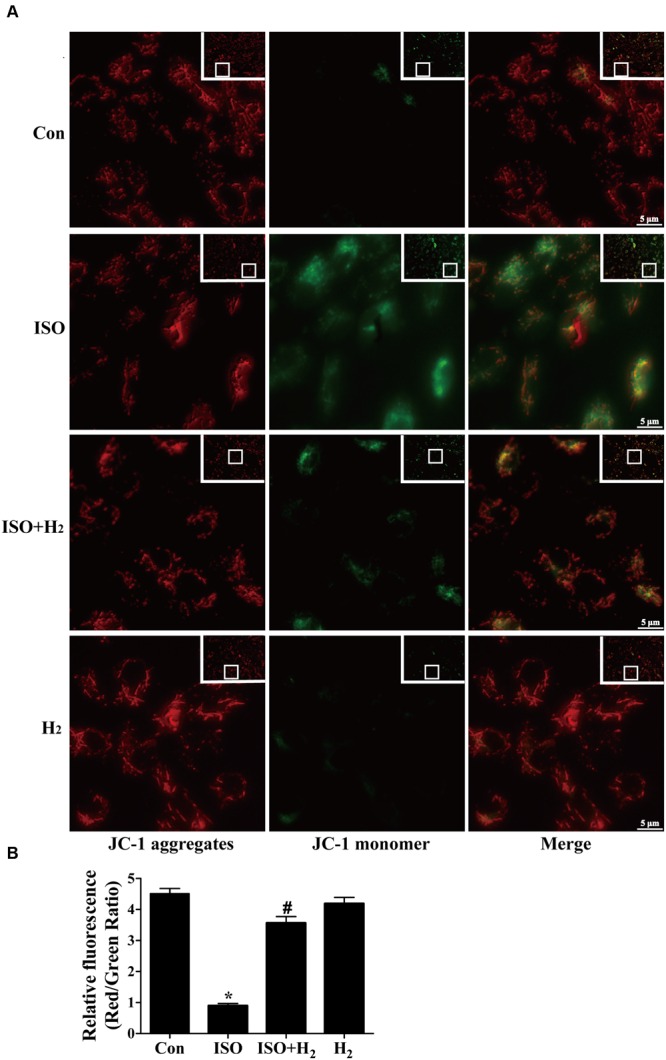

Measurement of MMP

Mitochondrial membrane potential was determined by the dye 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbo-cyanine iodide (JC-1) as previously described with slight modification (Cossarizza et al., 1993). Briefly, the treated cells were washed with PBS, and then incubated with JC-1 staining dye (culture medium: JC-1 working dye = 1:1) at 37°C in the dark for 20 min and rinsed three times with cold PBS, and analyzed by fluorescence microscope (Axio Observer Z1, Carl Zeiss. Inc.). The JC-1 aggregates, which was accumulated in the inner membrane of mitochondria, emitted red fluorescence and represented the high MMP, while green fluorescence reflected JC-1 monomer which entered in the cytosol following mitochondrial membrane depolarization. When mitochondria is damaged, the red/green ratio decreases. The ratio of JC-1 aggregates to monomer (red/green) intensity for each region was calculated by Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.0).

qRT-PCR

Total mRNA was extracted from left ventricles and H9c2 cardiomyocytes using TRIZol reagent (15596-026, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction, and cDNA was synthesized using oligo (dT) primers with the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (PrimeScriptTM RT Master Mix, Takara). Selected gene differences were confirmed by qRT-PCR using SYBR green (SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM, Takara). The target gene expression was normalized to GAPDH gene expression. The primers for qRT-PCR are shown in Table Table11.

Table 1

The primers for qRT-PCR.

| Name | Forward primer sequence (5′–3′) | Reverse primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| M-GAPDH | GGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCA | TGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACTCC |

| R-GAPDH | GACATGCCGCCTGGAGAAAC | AGCCCAGGATGCCCTTTAGT |

| M-ANP | GTCTTGCCTCTCCCACTCTG | TTCGTCCTTGGTGCTGAAGT |

| R-ANP | GGGAAGTCAACCCGTCTCA | GGCTCCAATCCTGTCAATCC |

| M-BNP | TCTGGGACCACCTTTGAAGT | ATGTTGTGGCAAGTTTGTGC |

| R-BNP | CTCCAGAACAATCCACGATG | ACAGCCCAAGCGACTGACT |

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2016). The membranes were incubated with primary (1:2000) and secondary (1:2000) antibodies by standard techniques. Immunodetection was accomplished using enhanced chemiluminescence (ChemiDoc XRS+ System, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Assessment of Cardiac ROS Levels

Cardiac total ROS was stained with dihydroethidium (DHE, D-23107; Invitrogen) on fresh frozen sections as previously described (Zhang et al., 2014). Images were immediately acquired using confocal microscopy (Leica Model SPE, Leica Imaging Systems Ltd) using λex 405 nm laser excitation.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Differences among groups were tested by one-way ANOVA. Comparisons between two groups were performed by unpaired Student’s t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be significantly different.

Results

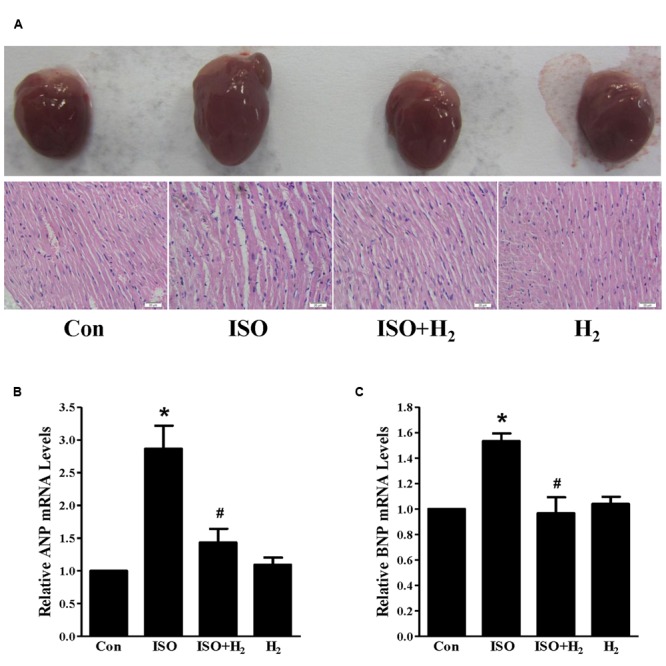

H2 inhibited Cardiac Hypertrophy In vivo

In order to investigate the effects of H2 on cardiac hypertrophy, ISO was used to induce cardiac hypertrophy in mice. As expected, mice with chronic ISO infusion exhibited cardiac hypertrophy compared to the control group, as indicated by the gross morphology of hearts, heart sections stained with H&E (Figure Figure1A1A). The hypertrophic marker gene ANP and BNP mRNA levels (Figures 1B,C, P < 0.05 vs. Con), and HW/BW ratio (Table Table22, P < 0.05 vs. Con) were also increased. Pretreatment with H2 (intraperitoneal injection) at the dose of 1 ml/100g/day reversed these hypertrophic responses (Figure Figure11Table Table22, P < 0.05 vs. ISO). Moreover, H2 injection alleviated the impaired left ventricular function, as evidenced by decreasing left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), and increasing fractional shortening (FS%; Table Table22, P < 0.05 vs. ISO). However, there were no significant changes between control group and H2 group. Collectively, these data suggested that H2 injection prevented the development of ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy and preserved cardiac function in vivo.

Effects of hydrogen (H2) on cardiac hypertrophy induced by isoproterenol (ISO) in vivo. (A) Gross morphology of hearts (top) and heart sections stained with H&E (bottom) after 1 week of ISO infusion with or without H2 at the dose of 1 ml/100g/day. (B) The relative mRNA expression of hypertrophic marker atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) to GAPDH (n = 3). (C) The relative mRNA expression of hypertrophic marker B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) to GAPDH (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05 vs. Control (Con) and #P < 0.05 vs. ISO. Scale bar: 20 μm.

Table 2

Effects of hydrogen on cardiac dysfunction induced by isoproterenol (ISO) in vivo.

| Parameter | Con | ISO | ISO+H2 | H2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| HW/BW (mg/g) | 4.72 ± 0.08 | 5.81 ± 0.07∗ | 5.09 ± 0.14# | 4.69 ± 0.06 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 3.24 ± 0.10 | 3.71 ± 0.06∗ | 3.45 ± 0.01# | 3.26 ± 0.08 |

| LVESD (mm) | 2.05 ± 0.05 | 2.52 ± 0.07∗ | 2.35 ± 0.04# | 2.12 ± 0.07 |

| FS (%) | 35.99 ± 0.13 | 31.56 ± 0.19∗ | 33.30 ± 0.45# | 35.68 ± 0.26 |

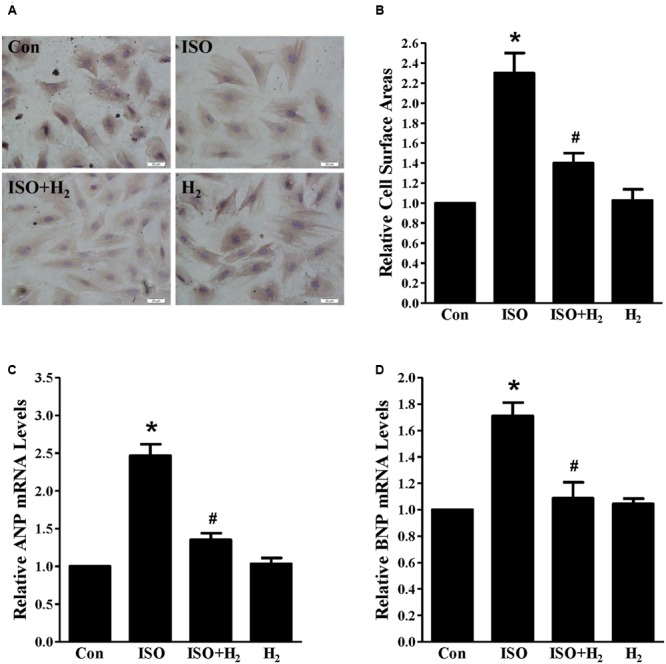

H2 attenuated Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy In vitro

As the heart primarily consists of cardiomyocyte and fibroblast, therefore, we investigated whether H2 could target cardiomyocyte for hypertrophic inhibition. H2-rich medium and H9c2 cardiomyocytes were used for in vitro studies. First, we used CCK8 to investigate the possible cytotoxity of H2-rich medium on H9c2 cardiomyocyte. H2 was shown to be non-cytotoxic for cardiomyocyte treating with H2-rich medium for 48 h (data not shown). After 48 h of ISO stimulation, cardiomyocyte surface areas, and the hypertrophic marker gene ANP and BNP mRNA levels were significantly increased in H9c2 cardiomyocyte (Figures 2A–D, P < 0.05 vs. Con). H2-rich medium attenuated these hypertrophic responses of H9c2 cardiomyocyte (Figures 2A–D, P < 0.05 vs. ISO). These data indicated that H2 could also inhibit ISO-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro.

Effects of H2-rich medium on cardiomyocytes hypertrophy induced by ISO in vitro. (A) Photomicrographs of morphological change induced by ISO with or without H2-rich medium. (B) Bar graph shows the relative cell surface area of cardiomyocytes stimulated by ISO with or without H2-rich medium. (C) The relative mRNA levels of hypertrophic marker ANP to GAPDH (n = 4). (D) The relative mRNA levels of hypertrophic marker BNP to GAPDH (n = 4). ∗P < 0.05 vs. Con and #P< 0.05 vs. ISO. Scale bar: 20 μm.

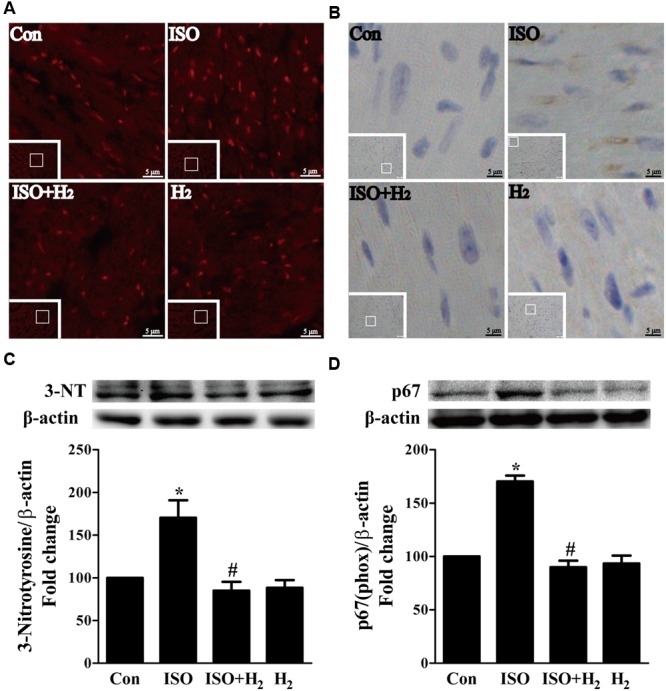

H2 Blocked the Excess ROS Accumulation and Mitochondrial Damage

ROS play a critical role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (Burgoyne et al., 2012). ROS levels were increased in the left ventricular of ISO-infused mice compared with control mice, and this increase was inhibited by pretreatment with H2 at the dose of 1ml/100g/day (Figure Figure3A3A). Moreover, another oxidative stress marker, 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT), which reflects the formation of ONOO–, was also upregulated by ISO stimuli, and suppressed by H2 (Figure Figure3B3B). To confirm these in vivo findings, we evaluated the effects of H2-rich medium on the levels of 3-NT stimulated by ISO in vitro. The accumulation of 3-NT was increased after ISO stimulation, while H2-rich medium attenuated this effects (Figure Figure3C3C, P < 0.05).

Effects of H2 on the generation of Reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by ISO both in vivo and in vitro. (A) Total ROS was stained with dihydroethidium (DHE) in the heart infused by ISO 1 week with or without H2 at the dose of 1 ml/100g/day. (B) Cardiac 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) was stained by immunohistochemistry in different groups. (C) Representative Western blotting and quantification of 3-NT to β-actin in H9c2 cardiomyocytes stimulated by ISO for 5 min with or without H2-rich medium for 30 min pretreatment (n = 4). (D) Representative Western blotting and quantification of p67 (phox) to β-actin in the hearts (n = 4). ∗P < 0.05 vs. Con and #P < 0.05 vs. ISO. Scale bar: 5 μm.

To further understand the mechanism of H2 in blocking ROS accumulation, we tested the NADPH oxidase subunit p67 (phox) expression. Immunoblotting revealed the expression of p67 (phox) was increased in left ventricular of ISO-infused mice, and this increase was alleviated by H2 (Figure Figure3D3D, P < 0.05). As we have mentioned above, NADPH oxidase-derived ROS can stimulate and amplify mitochondrial ROS production and induce mitochondrial dysfunction (Zorov et al., 2000Dai et al., 2011a), and these can be reflected by the change of MMP. ISO induced the depression of MMP, as indicated by high levels of green fluorescence and low levels of red fluorescence. Interestingly, H2-rich medium blocked the depression of MMP induced by ISO (Figures 4A,B, P < 0.05). Therefore, these data indicated that H2 inhibited the excess ROS accumulation following ISO stimuli through attenuating NADPH oxidase expression and mitochondrial damage.

Effects of H2-rich medium on ISO-induced depression of MMP in vitro. After stimulated by ISO for 24 h with or without H2-rich medium for 30 min pretreatment, MMP was measured by JC-1 staining followed by photofluorography (A). The quantification of the fluorescence intensity (red/green ratio) for each treatment was calculated by Image-Pro Plus software (B) (n = 4). ∗P < 0.05 vs. Con and #P < 0.05 vs. ISO. Scale bar: 5 μm.

H2 suppressed Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs) Signaling In vivo and In vitro

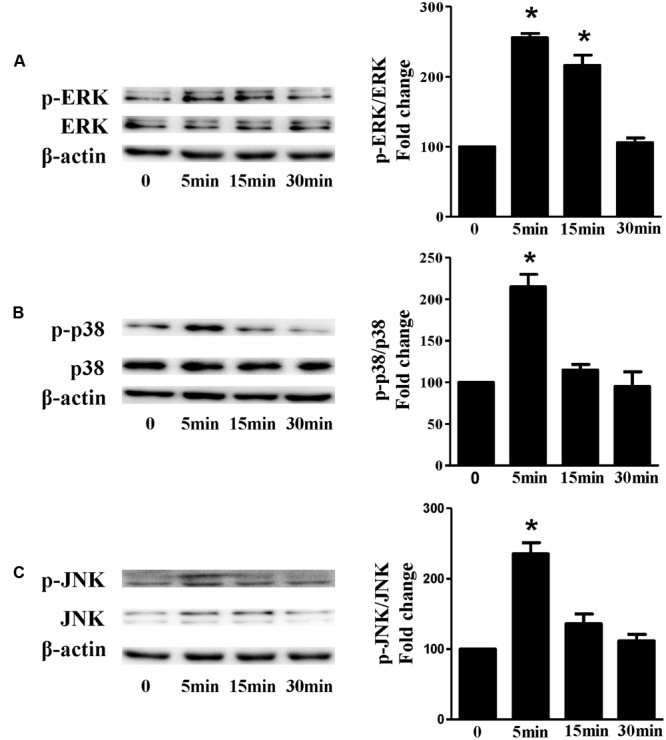

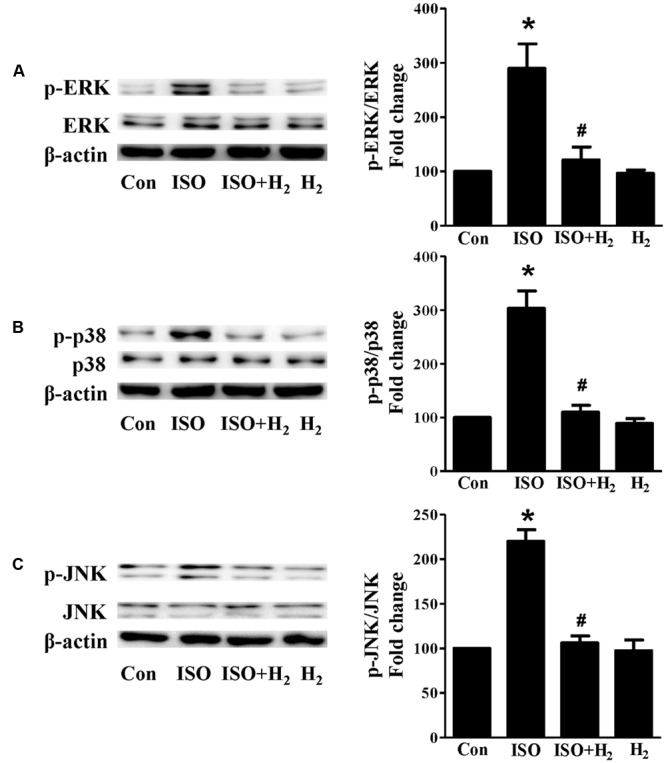

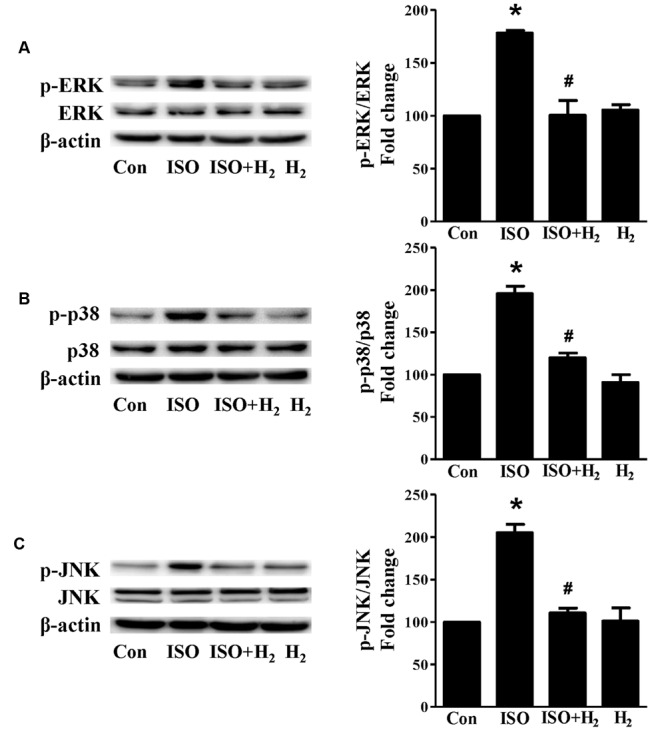

Based on the inhibitory effect of H2 on the ISO-induced excess accumulation of ROS in vitro and in vivo, we further investigated its effect on the downstream hypertrophic targets, such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) signaling pathways. Following ISO stimuli, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK (p38), and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) were increased to the high level at 5 min, and came to the base line at 30 min (Figure Figure55, P < 0.05 vs. 0 min). These enhanced activation of MAPKs could be blocked by H2-rich medium in vitro (Figure Figure66P < 0.05 vs. ISO). Similarly, the activation of MAPKs were enhanced in the hearts of ISO-infused mice compared with control group (Figure Figure77, P < 0.05 vs. Con). Such changes were inhibited by pretreatment with H2

in vivo (Figure Figure77, P < 0.05 vs. ISO). Thus, H2 suppressed the enhanced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38, and JNK to alleviate ISO-mediated cardiac hypertrophy in vivo and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro.

The time-dependent effects of ISO on MAPKs activation in vitro. Representative Western blot and quantification of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (A), or p38 phosphorylation (B), or JNK phosphorylation (C) to their total protein expressions, respectively, n = 4. ∗P < 0.05 vs. 0 min.

Effects of H2-rich medium on ISO-mediated MAPKs signaling activation in vitro. Representative Western blot and quantification of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (A), p38 phosphorylation (B), and JNK phosphorylation (C) to their total protein expressions, respectively, n = 4. ∗P < 0.05 vs. Con and #P < 0.05 vs. ISO.

Effects of H2 (1 ml/100g/day) on MAPKs signaling activation induced by ISO in vivo. Representative Western blotting and quantification of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (A), or p38 phosphorylation (B), or JNK phosphorylation (C) to their total protein expressions, respectively, n = 4. ∗P < 0.05 vs. Con and #P < 0.05 vs. ISO.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that intraperitoneal injection of H2 protects against ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in vivo and H2-rich medium attenuates ISO-mediated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro. The cardioprotection of H2 is mediated by direct interruption of NADPH oxidase expression and alleviating mitochondrial damage, these lead to inhibit the accumulation of ROS, and subsequently block downstream ERK1/2, p38, and JNK signaling.

H2 has been emerged as an important blocker of heart diseases by various given manners. H2 inhalation attenuates intermittent hypoxia (Hayashi et al., 2011Kato et al., 2014), or ischemia/reperfusion (Hayashida et al., 2008), or germinal matrix hemorrhage-induced left ventricular remodeling (Lekic et al., 2011). Drinking H2-rich water blocks cardiac fibrosis induced by left kidney artery ischemia/reperfusion injury (Zhu et al., 2011). H2-rich saline injection also inhibits ischemia/reperfusion (Sun et al., 2009), or hypertension-mediated cardiac remodeling (Wang et al., 2011Yu and Zheng, 2012). However, the effects of intraperitoneal injection of H2 on cardiac hypertrophy induced by β-adrenoceptor stimulation have not yet been clarified. In this study, we prepared H2-rich medium, and developed new methods for giving H2

in vivo by intraperitoneal injection of H2, and we find that H2 not only attenuates ISO-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro and cardiac hypertrophy in vivo, but also improves the impaired cardiac function. As we have mentioned above, diabetic cardiomyopathy is also a contributor to cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. H2-rich saline has been reported to improve early neurovascular dysfunction (Feng et al., 2013) and erectile dysfunction (Fan et al., 2013) in a streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat model. However, the effect of H2 on diabetic cardiomyopathy is still under investigation. It has been reported that the gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide (H2S) protects against pressure overload-mediated (Kondo et al., 2013) or arteriovenous fistula (AVF)-induced heart failure (Mishra et al., 2010). A question raised here is that whether the reciprocal interaction between H2 and H2S exists during their regulation of cardiac hypertrophy.

The excess activation of ROS has been shown to contribute to the development of cardiac hypertrophy (Li et al., 2002Zhang et al., 2005, 2007bBurgoyne et al., 2012). In this study, we reveal that H2 blocks ROS accumulation induced by β-adrenoceptor stimulation both in vitro and in vivo. The inhibitory effects of H2 on ROS also have been reported in various animal models, such as heart ischemia/reperfusion injury (Zhang et al., 2011Noda et al., 2013Shinbo et al., 2013), brain injury (Ohsawa et al., 2007Liu et al., 2011Wang et al., 2012), renal injury (Li et al., 2016), chemotherapy-induced ovarian injury (Meng et al., 2015), metabolic syndrome (Song et al., 2013), etc. NADPH oxidase and mitochondria have been proposed as primary sites of ROS generation (Dai et al., 2011a). ROS produced by NADPH oxidase has the ability to stimulate and amplify mitochondrial ROS generation and induce mitochondrial dysfunction (Zorov et al., 2000Dai et al., 2011a). Therefore, tyrosine kinase FYN interacts with the C-terminal domain of NOX4, and phosphorylates the tyrosine 566 on NOX4, thereby inhibiting apoptosis in the heart and preventing cardiac remodeling after pressure overload (Matsushima et al., 2016). Overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria, but not the overexpression of wild-type peroxisomal catalase, protects against ANG II-induced cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and mitochondrial damage, as well as heart failure induced by overexpression of Gαq (Dai et al., 2011b). We found that H2 inhibits ISO-induced NADPH oxidase subunit p67 expression, and suppresses the dissipation of MMP.

The excessive accumulation of ROS subsequently transmits signals to downstream ROS-sensitive signaling pathways, such as ERK1/2 (Li et al., 2002Dai et al., 2011b), p38 MAPK (Li et al., 2002Dai et al., 2011a), and JNK (Li et al., 2002Kimura et al., 2005Zhang et al., 2007a), NF-κB (Hirotani et al., 2002), PI3K/Akt (Sundaresan et al., 2009Wang et al., 2013), and autophagy related signaling (Dai et al., 2011b), to induce pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Our results indicate that H2 markedly blocks ISO-induced ERK1/2, p38 and JNK activation in vivo and in vitro. These findings confirm that the anti-hypertrophic effect of H2 is partially achieved through blocking ROS-dependent MAPKs signaling. Yu Yongsheng et al. has reported that H2-rich saline inhibits cardiac hypertrophy in spontaneous hypertensive rats (SHRs) via blocking NF-κB activity (Yu and Zheng, 2012). H2-rich saline reduces myocardial reperfusion injury and improves heart function through down-regulating the expression of Akt and GSK3β (Yue et al., 2015), and blocking autophagy in myocardial tissue (Pan et al., 2015). However, whether PI3K/Akt, and autophagy signaling are related to the protective effects of H2 injection on pathological cardiac hypertrophy still needs further investigation.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that intraperitoneal injection of H2 attenuated β-adrenoceptor agonist (ISO)-mediated cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in vivo, and H2-rich medium blocked ISO-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophic responses in vitro. Our results suggested that H2 exerted anti-hypertrophic activity, at least in part, via alleviating NADPH oxidase expression and inhibiting the depression of MMP, and thus blocked ROS-sensitive MAPK signaling pathways.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: YZ and TW. Performed the experiments: YZ, JX, ZL, and CW. Analyzed the data: YZ and JX. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: LW, PS, and PL.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We should thank Xuejun Sun (Second Military Medical University, China) and Guoqing Huang (Central South University, China) for helpful discussions and excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (To Tinghuai Wang, NO. 81572585, NO. 81372818).

References

- Akimoto H., Ito H., Tanaka M., Adachi S., Hata M., Lin M., et al. (1996). Heparin and heparan sulfate block angiotensin ii-induced hypertrophy in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. A possible role of intrinsic heparin-like molecules in regulation of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

Circulation

93

810–816. 10.1161/01.CIR.93.4.810 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Ambrosy A. P., Fonarow G. C., Butler J., Chioncel O., Greene S. J., Vaduganathan M., et al. (2014). The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries.

J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.

63

1123–1133. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.053 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Burgoyne J. R., Mongue-Din H., Eaton P., Shah A. M. (2012). Redox signaling in cardiac physiology and pathology.

Circ. Res.

111

1091–1106. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.255216 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Cossarizza A., Baccarani-Contri M., Kalashnikova G., Franceschi C. (1993). A new method for the cytofluorimetric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using the j-aggregate forming lipophilic cation 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide (jc-1).

Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.

197

40–45. 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2438 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Dai D. F., Chen T., Szeto H., Nieves-Cintrón M., Kutyavin V., Santana L. F., et al. (2011a). Mitochondrial targeted antioxidant peptide ameliorates hypertensive cardiomyopathy.

J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.

58

73–82. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.044 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Dai D. F., Johnson S. C., Villarin J. J., Chin M. T., Nieves-Cintrón M., Chen T., et al. (2011b). Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediates angiotensin ii-induced cardiac hypertrophy and galphaq overexpression-induced heart failure.

Circ. Res.

108

837–846. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.232306 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Fan M., Xu X., He X., Chen L., Qian L., Liu J., et al. (2013). Protective effects of hydrogen-rich saline against erectile dysfunction in a streptozotocin induced diabetic rat model.

J. Urol.

190

350–356. 10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Feng Y., Wang R., Xu J., Sun J., Xu T., Gu Q., et al. (2013). Hydrogen-rich saline prevents early neurovascular dysfunction resulting from inhibition of oxidative stress in stz-diabetic rats.

Curr. Eye Res.

38

396–404. 10.3109/02713683.2012.748919 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Frey N., Olson E. N. (2003). Cardiac hypertrophy: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Annu. Rev. Physiol.

65

45–79. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142243 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Hayashi T., Yoshioka T., Hasegawa K., Miyamura M., Mori T., Ukimura A., et al. (2011). Inhalation of hydrogen gas attenuates left ventricular remodeling induced by intermittent hypoxia in mice.

Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.

301

H1062–H1069. 10.1152/ajpheart.00150.2011 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Hayashida K., Sano M., Ohsawa I., Shinmura K., Tamaki K., Kimura K., et al. (2008). Inhalation of hydrogen gas reduces infarct size in the rat model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.

373

30–35. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.165 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Heineke J., Molkentin J. D. (2006). Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways.

Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.

7

589–600. 10.1038/nrm1983 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Hirotani S., Otsu K., Nishida K., Higuchi Y., Morita T., Nakayama H., et al. (2002). Involvement of nuclear factor-kappab and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in g-protein-coupled receptor agonist-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

Circulation

105

509–515. 10.1161/hc0402.102863 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Huang G., Zhou J., Zhan W., Xiong Y., Hu C., Li X., et al. (2013). The neuroprotective effects of intraperitoneal injection of hydrogen in rabbits with cardiac arrest.

Resuscitation

84

690–695. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.10.018 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Jeong K., Kwon H., Min C., Pak Y. (2009). Modulation of the caveolin-3 localization to caveolae and stat3 to mitochondria by catecholamine-induced cardiac hypertrophy in h9c2 cardiomyoblasts.

Exp. Mol. Med.

41

226–235. 10.3858/emm.2009.41.4.025 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Kato R., Nomura A., Sakamoto A., Yasuda Y., Amatani K., Nagai S., et al. (2014). Hydrogen gas attenuates embryonic gene expression and prevents left ventricular remodeling induced by intermittent hypoxia in cardiomyopathic hamsters.

Am. J. physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.

00228

2014

10.1152/ajpheart.00228.2014 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Kimura S., Zhang G. X., Nishiyama A., Shokoji T., Yao L., Fan Y. Y., et al. (2005). Role of nad(p)h oxidase- and mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species in cardioprotection of ischemic reperfusion injury by angiotensin ii.

Hypertension

45

860–866. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000163462.98381.7f [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Kondo K., Bhushan S., King A. L., Prabhu S. D., Hamid T., Koenig S., et al. (2013). H(2)s protects against pressure overload-induced heart failure via upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

Circulation

127

1116–1127. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000855 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Lekic T., Manaenko A., Rolland W., Fathali N., Peterson M., Tang J., et al. (2011). Protective effect of hydrogen gas therapy after germinal matrix hemorrhage in neonatal rats.

Acta Neurochir. Suppl.

111

237–241. 10.1007/978-3-7091-0693-8_40 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Li J., Hong Z., Liu H., Zhou J., Cui L., Yuan S., et al. (2016). Hydrogen-rich saline promotes the recovery of renal function after ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats via anti-apoptosis and anti-inflammation.

Front. Pharmacol.

7:106

10.3389/fphar.2016.00106 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Li J. M., Gall N. P., Grieve D. J., Chen M., Shah A. M. (2002). Activation of nadph oxidase during progression of cardiac hypertrophy to failure.

Hypertension

40

477–484. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000032031.30374.32 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Liu W., Chen O., Chen C., Wu B., Tang J., Zhang J. H. (2011). Protective effects of hydrogen on fetal brain injury during maternal hypoxia.

Acta Neurochir. Suppl.

111

307–311. 10.1007/978-3-7091-0693-8_51 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Magga J., Vuolteenaho O., Tokola H., Marttila M., Ruskoaho H. (1998). B-type natriuretic peptide: a myocyte-specific marker for characterizing load-induced alterations in cardiac gene expression.

Ann. Med.

30(Suppl. 1)

39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Matsushima S., Kuroda J., Zhai P., Liu T., Ikeda S., Nagarajan N., et al. (2016). Tyrosine kinase fyn negatively regulates nox4 in cardiac remodeling.

J. clin. Invest.

126

3403–3416. 10.1172/JCI85624 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Meng X., Chen H., Wang G., Yu Y., Xie K. (2015). Hydrogen-rich saline attenuates chemotherapy-induced ovarian injury via regulation of oxidative stress.

Exp. Ther. Med.

10

2277–2282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Mishra P. K., Tyagi N., Sen U., Givvimani S., Tyagi S. C. (2010). H2s ameliorates oxidative and proteolytic stresses and protects the heart against adverse remodeling in chronic heart failure.

Am. J. physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.

298

H451–H456. 10.1152/ajpheart.00682.2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Noda K., Shigemura N., Tanaka Y., Kawamura T., Hyun Lim S., Kokubo K.,et al. (2013). A novel method of preserving cardiac grafts using a hydrogen-rich water bath.

J. Heart Lung Transplant.

32

241–250. 10.1016/j.healun.2012.11.004 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Ohsawa I., Ishikawa M., Takahashi K., Watanabe M., Nishimaki K., Yamagata K., et al. (2007). Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals.

Nat. Med.

13

688–694. 10.1038/nm1577 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Ohta S. (2015). Molecular hydrogen as a novel antioxidant: overview of the advantages of hydrogen for medical applications.

Methods Enzymol.

555

289–317. 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.038 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Pan Z., Zhao Y., Yu H., Liu D., Xu H. (2015). [effect of hydrogen-rich saline on cardiomyocyte autophagy during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in aged rats].

Zhonghua yi xue za zhi

95

2022–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Shinbo T., Kokubo K., Sato Y., Hagiri S., Hataishi R., Hirose M., et al. (2013). Breathing nitric oxide plus hydrogen gas reduces ischemia-reperfusion injury and nitrotyrosine production in murine heart.

Am. J. physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.

305

H542–H550. 10.1152/ajpheart.00844.2012 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Song G., Li M., Sang H., Zhang L., Li X., Yao S., et al. (2013). Hydrogen-rich water decreases serum ldl-cholesterol levels and improves hdl function in patients with potential metabolic syndrome.

J. Lipid Res.

54

1884–1893. 10.1194/jlr.M036640 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Sun Q., Kang Z., Cai J., Liu W., Liu Y., Zhang J. H., et al. (2009). Hydrogen-rich saline protects myocardium against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats.

Exp. Biol. Med.

234

1212–1219. 10.3181/0812-RM-349 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Sundaresan N. R., Gupta M., Kim G., Rajamohan S. B., Isbatan A., Gupta M. P. (2009). Sirt3 blocks the cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting foxo3a-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms in mice.

J. Clin. Investig.

119

2758–2771. 10.1172/JCI39162 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Tshori S., Gilon D., Beeri R., Nechushtan H., Kaluzhny D., Pikarsky E., et al. (2006). Transcription factor mitf regulates cardiac growth and hypertrophy.

J. Clin. Investig.

116

2673–2681. 10.1172/JCI27643 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Wang H. X., Yang H., Han Q. Y., Li N., Jiang X., Tian C., et al. (2013). Nadph oxidases mediate a cellular “memory” of angiotensin ii stress in hypertensive cardiac hypertrophy.

Free radic. Biol. Med.

65

897–907. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.08.179 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Wang W., Li Y., Ren J., Xia F., Li J., Zhang Z. (2012). Hydrogen rich saline reduces immune-mediated brain injury in rats with acute carbon monoxide poisoning.

Neurol. Res.

34

1007–1015. 10.1179/1743132812Y.0000000106 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Wang Y., Jing L., Zhao X. M., Han J. J., Xia Z. L., Qin S. C., et al. (2011). Protective effects of hydrogen-rich saline on monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in a rat model.

Respir. Res.

12

26

10.1186/1465-9921-12-26 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Webb I. G., Nishino Y., Clark J. E., Murdoch C., Walker S. J., Makowski M. R., et al. (2010). Constitutive glycogen synthase kinase-3alpha/beta activity protects against chronic beta-adrenergic remodelling of the heart.

Cardiovasc. Res.

87

494–503. 10.1093/cvr/cvq061 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Yu Y. S., Zheng H. (2012). Chronic hydrogen-rich saline treatment reduces oxidative stress and attenuates left ventricular hypertrophy in spontaneous hypertensive rats.

Mol. Cell. Biochem.

365

233–242. 10.1007/s11010-012-1264-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Yue L., Li H., Zhao Y., Li J., Wang B. (2015). [effects of hydrogen-rich saline on akt/gsk3beta signaling pathways and cardiac function during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in rats].

Zhonghua yi xue za zhi

95

1483–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Zhang G. X., Kimura S., Nishiyama A., Shokoji T., Rahman M., Yao L., et al. (2005). Cardiac oxidative stress in acute and chronic isoproterenol-infused rats.

Cardiovasc. Res.

65

230–238. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.013 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Zhang G. X., Lu X. M., Kimura S., Nishiyama A. (2007a). Role of mitochondria in angiotensin ii-induced reactive oxygen species and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation.

Cardiovasc. Res.

76

204–212. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.07.014 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Zhang G. X., Ohmori K., Nagai Y., Fujisawa Y., Nishiyama A., Abe Y., et al. (2007b). Role of at1 receptor in isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy and oxidative stress in mice.

J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol.

42

804–811. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.01.012 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Zhang Y., Sun Q., He B., Xiao J., Wang Z., Sun X. (2011). Anti-inflammatory effect of hydrogen-rich saline in a rat model of regional myocardial ischemia and reperfusion.

Int. J. Cardiol

148

91–95. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.08.058 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Zhang Y., Xu J., Luo Y. X., An X. Z., Zhang R., Liu G., et al. (2014). Overexpression of mitofilin in the mouse heart promotes cardiac hypertrophy in response to hypertrophic stimuli.

Antioxid. Redox Signal.

21

1693–1707. 10.1089/ars.2013.5438 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Zhang Y., Zhang X. J., Li H. (2015). Targeting interferon regulatory factor for cardiometabolic diseases: opportunities and challenges.

Curr. Drug Targets

10.2174/1389450117666160701092102

[Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Zhang Y. X., Xu J. T., You X. C., Wang C., Zhou K. W., Li P., et al. (2016). Inhibitory effects of hydrogen on proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells via down-regulation of mitogen/activated protein kinase and ezrin-radixin-moesin signaling pathways.

Chin. J. Physiol.

59

46–55. 10.4077/CJP.2016.BAE365 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Zhu W. J., Nakayama M., Mori T., Nakayama K., Katoh J., Murata Y., et al. (2011). Intake of water with high levels of dissolved hydrogen (h2) suppresses ischemia-induced cardio-renal injury in dahl salt-sensitive rats.

Nephrol. Dial. Transplant.

26

2112–2118. 10.1093/ndt/gfq727 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Zorov D. B., Filburn C. R., Klotz L. O., Zweier J. L., Sollott S. J. (2000). Reactive oxygen species (ros)-induced ros release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes.

J. Exp. Med.

192

1001–1014. 10.1084/jem.192.7.1001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

The Original Article:

original title: Hydrogen (H2) Inhibits Isoproterenol-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy via Antioxidative Pathways

Yaxing Zhang, Jingting Xu, Zhiyuan Long, Chen Wang, Ling Wang, Peng Sun, Peng Li, Tinghuai Wang

-

Abstract:

Background and Purpose:

Hydrogen (H2) has been shown to have a strong antioxidant effect on preventing oxidative stress-related diseases. The goal of the present study is to determine the pharmacodynamics of H2 in a model of isoproterenol (ISO)-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Methods:

Mice (C57BL/6J; 8–10 weeks of age) were randomly assigned to four groups: Control group (n = 10), ISO group (n = 12), ISO plus H2 group (n = 12), and H2 group (n = 12). Mice received H2 (1 ml/100g/day, intraperitoneal injection) for 7 days before ISO (0.5 mg/100g/day, subcutaneous injection) infusion, and then received ISO with or without H2 for another 7 days. Then, cardiac function was evaluated by echocardiography. Cardiac hypertrophy was reflected by heart weight/body weight, gross morphology of hearts, and heart sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and relative atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) mRNA levels. Cardiac reactive oxygen species (ROS), 3-nitrotyrosine and p67 (phox) levels were analyzed by dihydroethidium staining, immunohistochemistry and Western blotting, respectively. For in vitro study, H9c2 cardiomyocytes were pretreated with H2-rich medium for 30 min, and then treated with ISO (10 μM) for the indicated time. The medium and ISO were re-changed every 24 h. Cardiomyocyte surface areas, relative ANP and BNP mRNA levels, the expression of 3-nitrotyrosine, and the dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) were examined. Moreover, the expression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 (ERK1/2), p-ERK1/2, p38, p-p38, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), and p-JNK were measured by Western blotting both in vivo and in vitro. Results:

Intraperitoneal injection of H2 prevented cardiac hypertrophy and improved cardiac function in ISO-infused mice. H2-rich medium blocked ISO-mediated cardiomyocytes hypertrophy in vitro. H2 blocked the excessive expression of NADPH oxidase and the accumulation of ROS, attenuated the decrease of MMP, and inhibited ROS-sensitive ERK1/2, p38, and JNK signaling pathways. Conclusion:

H2 inhibits ISO-induced cardiac/cardiomyocytes hypertrophy both in vivo and in vitro, and improves the impaired left ventricular function. H2 exerts its protective effects partially through blocking ROS-sensitive ERK1/2, p38, and JNK signaling pathways.